When it comes to metabolic health, blood sugar regulation stands as one of the most critical processes the body manages daily. For individuals without diabetes, blood sugar levels typically stay within a narrow range, thanks to the harmonious interaction between insulin production, cellular glucose uptake, and hepatic glucose control. However, this finely tuned system is vulnerable to disruption. One of the most overlooked triggers for abnormal blood sugar spikes is illness. Whether from a common cold or a severe infection, the body’s inflammatory and immune responses can significantly alter glucose dynamics. Understanding how illness affects blood sugar is essential not just for individuals living with diabetes but also for those seeking to understand how infection and inflammation can lead to temporary or sustained hyperglycemia. The question of whether an infection can cause high blood sugar is more than academic—it has meaningful implications for clinical treatment, recovery timelines, and long-term metabolic health.

You may also like: How Diabetes Affects the Brain: Understanding Brain Fog, Memory Loss, and Mental Confusion from High Blood Sugar

The Science of Stress Responses and Glucose Elevation

To understand how infections can cause high blood sugar levels, it helps to explore the body’s natural response to illness. When the immune system detects pathogens—whether viral, bacterial, or fungal—it triggers an inflammatory cascade aimed at neutralizing the threat. As part of this cascade, stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline are released in abundance. These hormones promote gluconeogenesis, a metabolic pathway in the liver that generates glucose from non-carbohydrate substrates. This process ensures that cells—especially immune cells and those in the brain—have a ready supply of energy during times of stress.

While this response is adaptive in the short term, it also comes with unintended consequences. Elevated levels of cortisol impair the action of insulin, leading to reduced cellular glucose uptake and a corresponding increase in circulating blood sugar. Infections, therefore, create a physiological state where glucose is produced more readily but is less effectively utilized. This dual impact is one of the main reasons an infection can cause high blood sugar levels, even in people who do not have a history of diabetes.

Immune-Mediated Insulin Resistance During Infection

The concept of insulin resistance is often associated with chronic conditions like type 2 diabetes and obesity, but it also plays a transient role in response to acute illness. When the body is fighting off an infection, pro-inflammatory cytokines—such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), and C-reactive protein—are released in large quantities. These cytokines interfere with insulin signaling pathways in muscle and fat tissue, causing a temporary form of insulin resistance.

In this context, even if insulin is being secreted normally by the pancreas, the body’s tissues do not respond to it effectively. This phenomenon has been well-documented in clinical settings, particularly in patients hospitalized with sepsis, pneumonia, or even urinary tract infections. The presence of elevated blood glucose in these cases, despite normal insulin production, highlights how illness affects blood sugar by altering the body’s response to its own hormones.

This transient insulin resistance serves an evolutionary purpose: it allows glucose to be diverted away from muscle and fat cells and toward immune cells that are actively fighting the infection. However, the consequence is that glucose levels in the bloodstream can remain elevated for days or even weeks. This explains why even minor infections, such as a sinus infection or influenza, can lead to unexplained blood sugar spikes.

Liver Function, Inflammatory Signals, and Glucose Regulation

The liver plays a central role in maintaining glucose homeostasis, and its behavior changes significantly during illness. Under normal conditions, the liver balances glucose output through a finely tuned interplay of insulin and glucagon signaling. However, infections disrupt this balance by sending pro-inflammatory signals that override insulin’s suppressive effect on hepatic glucose production.

When immune activation is in full swing, the liver ramps up gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis—breaking down glycogen into glucose. This hepatic overdrive further contributes to hyperglycemia. In individuals with prediabetes or other metabolic dysfunctions, this can push glucose levels into dangerously high territory, revealing just how profound the impact of illness can be.

Clinicians are particularly mindful of this mechanism in patients recovering from surgery, trauma, or systemic infections. Not only does it complicate glucose control, but it also prolongs hospital stays and impairs wound healing. Research has shown that tighter glucose regulation in critically ill patients correlates with better outcomes, reinforcing the idea that understanding how illness affects blood sugar has direct implications for treatment protocols.

The Role of Fever, Appetite Loss, and Dehydration

Beyond hormonal and cellular pathways, the symptoms of illness themselves can contribute to changes in glucose regulation. Fever increases basal metabolic rate, causing the body to burn through glucose stores more rapidly. At the same time, illness often leads to reduced appetite, causing a mismatch between glucose output and intake. When food intake is low, insulin secretion may also drop, removing one of the critical checks against rising blood sugar.

Dehydration, a common consequence of both fever and gastrointestinal illnesses, further complicates glucose control. As water is lost through sweating, vomiting, or diarrhea, blood becomes more concentrated. This hemoconcentration artificially raises measured blood glucose levels and can exacerbate symptoms of hyperglycemia. In hospital settings, rehydration is often a first-line intervention to help stabilize blood sugar in patients with infections.

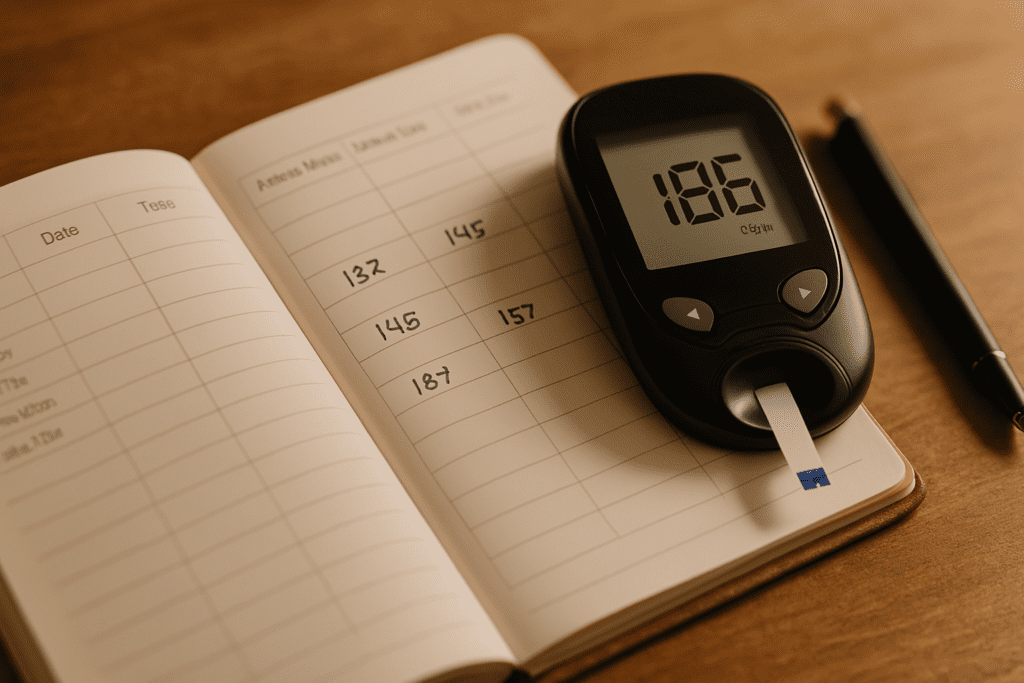

Together, these factors explain why the question “can infection raise blood sugar” is not just theoretically valid but practically significant. Even short-term illness can disrupt glucose balance in multiple ways, highlighting the need for proactive monitoring and intervention.

Why Healthy Individuals Should Care About Temporary Hyperglycemia

It’s easy to assume that blood sugar fluctuations during illness are only a concern for people with diabetes, but this perspective overlooks the broader implications of glucose dysregulation. Studies have shown that even in healthy individuals, transient episodes of hyperglycemia—especially when repeated—can increase the risk of endothelial damage, promote oxidative stress, and impair immune function.

This suggests that the effects of illness on blood sugar may create a feedback loop: infection causes high blood sugar, which in turn impairs the body’s ability to fight the infection. Recognizing and interrupting this cycle could be critical, especially during pandemics or flu seasons, when even mild infections are widespread. Moreover, repeated spikes in glucose levels can contribute to insulin resistance over time, particularly when coupled with other risk factors like poor diet or sedentary lifestyle.

From a public health perspective, these findings reinforce the importance of metabolic health as a buffer against infectious disease. Keeping blood sugar within a stable range, even during periods of illness, may help reduce the risk of complications and speed up recovery. For this reason alone, knowing whether an infection can cause high blood sugar levels should be part of every individual’s health literacy.

Clinical Implications for Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Patients

For people with diabetes, the question of how illness affects blood sugar is not hypothetical but urgent. Infections often lead to what is known as “sick-day hyperglycemia,” a condition where glucose levels rise dramatically due to stress responses, insulin resistance, and changes in medication adherence. These spikes can be dangerous, leading to complications like diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS).

However, even individuals without a diabetes diagnosis may find their glucose levels entering the prediabetic or diabetic range temporarily. This is especially common in hospital settings, where close monitoring often reveals elevated glucose in patients admitted for infections, trauma, or surgery. These findings underscore the importance of monitoring glucose as a vital sign during illness.

For clinicians, this means integrating glucose management into standard protocols for treating infections. It also means that glucose-lowering interventions—ranging from hydration and dietary adjustments to insulin therapy—may be warranted even in non-diabetic patients under acute stress. Recognizing that an infection can cause high blood sugar opens the door to more proactive and effective medical care.

Post-Illness Recovery and Glucose Stabilization

Once the acute phase of an illness has passed, blood sugar typically begins to normalize. However, the return to baseline can be delayed, particularly in individuals with underlying insulin resistance or metabolic syndrome. Prolonged stress responses, reduced physical activity during recovery, and residual inflammation can all extend the period of glucose dysregulation.

This post-illness window presents an important opportunity for intervention. Simple lifestyle changes, such as gradually reintroducing exercise, maintaining a balanced diet, and ensuring adequate sleep, can support the re-stabilization of glucose levels. In some cases, follow-up glucose testing may be warranted to assess whether levels have fully returned to normal.

This phase also presents a valuable moment for health education. Patients who experience unexplained high blood sugar during illness may benefit from understanding that the phenomenon is both common and manageable. Still, they should be encouraged to monitor for persistent hyperglycemia, which could indicate an underlying metabolic issue that warrants further investigation.

Frequently Asked Questions: Infections, Illness, and Blood Sugar—What You Might Not Know

1. How does the body’s immune response to infection influence blood sugar regulation over time?

When the immune system detects an infection, it initiates a complex cascade of inflammatory responses that can directly impact glucose metabolism. This heightened immune activity causes the release of stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline, which promote insulin resistance. Over time, this resistance can make it harder for cells to absorb glucose, leading to elevated blood sugar levels even in those without diabetes. Research increasingly supports the notion that chronic or repeated infections may have long-term effects on insulin sensitivity. This deeper look into how illness affects blood sugar reveals that even mild infections may have cumulative metabolic consequences if not properly managed.

2. Can infection raise blood sugar levels even in individuals without diabetes?

Yes, even in people without diabetes, infections can lead to transient hyperglycemia. During an acute infection, the body reacts by releasing glucose into the bloodstream to provide quick energy for immune cells. In this context, the question “can infection raise blood sugar” becomes highly relevant across all populations. The response may not lead to a formal diagnosis of diabetes, but it can result in temporary elevations that could be mistaken for diabetic levels. Clinicians often monitor blood glucose during hospitalization for infections—even in non-diabetic patients—because these shifts can influence healing time, immune function, and medication efficacy.

3. What types of infections are most likely to elevate blood sugar significantly?

Bacterial infections, particularly urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and skin infections like cellulitis, are notorious for disrupting glucose control. These infections often provoke a strong inflammatory response, making the question “can infection cause high blood sugar” especially pertinent in these cases. Viral infections such as influenza or COVID-19 can also raise blood sugar, particularly if they cause fever and dehydration. Fungal infections, while less common, can persist longer and lead to chronic blood sugar elevations. Understanding which pathogens most affect glucose levels is essential in both diabetes management and general internal medicine.

4. Why does high blood sugar often go unnoticed during illness?

During illness, patients and even healthcare providers often attribute fatigue, frequent urination, or dehydration to the infection itself, overlooking the role of elevated glucose. This makes exploring how illness affects blood sugar all the more critical. Symptoms of hyperglycemia can overlap with those of infection, masking the underlying metabolic disturbance. Additionally, appetite loss or erratic eating patterns during illness may delay blood sugar testing. Without proactive monitoring, elevated glucose can worsen the infection or delay recovery, perpetuating a cycle that’s easy to miss in outpatient settings.

5. Can an infection cause high blood sugar levels that linger after the illness resolves?

Yes, in some cases, elevated blood sugar levels persist even after the acute infection has cleared. This phenomenon is especially common in individuals with prediabetes or underlying insulin resistance. Asking whether an infection can cause high blood sugar levels beyond the illness window leads to important conversations about long-term metabolic risk. Residual inflammation and changes in gut microbiota after illness may impair glucose regulation temporarily or even permanently. For individuals at risk, follow-up testing after recovery is critical to ensure that blood sugar levels return to baseline.

6. Are blood sugar spikes during infection more dangerous for people with diabetes?

Absolutely. For individuals with diabetes, the question isn’t just “can infection cause high blood sugar?” but how severely it can destabilize their condition. Illness-related spikes in glucose can increase the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS), both of which are medical emergencies. Moreover, infections can interfere with routine diabetes management, from altered meal patterns to medication absorption issues. In these cases, how illness affects blood sugar can lead to critical complications if not closely monitored and managed with adjustments to insulin or oral medications.

7. What role does dehydration play in infection-related blood sugar changes?

Dehydration is a major, often underappreciated factor in how illness affects blood sugar. Fever, vomiting, or diarrhea—all common during infections—reduce total body water, concentrating glucose in the bloodstream. This creates a feedback loop where high blood sugar causes more frequent urination, which in turn worsens dehydration. So, when asking “can infection raise blood sugar?” it’s crucial to consider hydration status as both a cause and consequence of elevated glucose. Staying well-hydrated during illness can help moderate blood sugar fluctuations and support kidney function, which is essential for glucose clearance.

8. How do antibiotics and antiviral medications influence blood sugar during infection?

Medications prescribed to treat infections can inadvertently alter blood sugar control. Some antibiotics, particularly fluoroquinolones, have been linked to both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. For people managing diabetes, this complicates the relationship between infection and glucose levels. It’s not only the illness itself—how illness affects blood sugar can also depend on the pharmacologic treatment chosen. Antiviral medications, especially in cases of herpes or HIV, may influence liver enzymes involved in glucose metabolism. Patients and clinicians alike must consider how medications interact with the body’s stress response to infection.

9. Are there strategies to prevent blood sugar spikes during an infection?

Yes, proactive strategies can help maintain stable glucose levels during illness. These include frequent blood sugar monitoring, maintaining hydration, and using a “sick day” diabetes plan with adjusted insulin doses or carbohydrate intake. People often ask, “Can an infection cause high blood sugar levels every time?” While not inevitable, being unprepared increases the likelihood. Even without a diabetes diagnosis, staying ahead of symptoms—especially in those with metabolic syndrome or obesity—can help minimize glucose volatility. Prevention also involves treating infections early, before they provoke a full systemic stress response.

10. What long-term research is being done on infections and blood sugar regulation?

Ongoing research is exploring how the immune system’s interaction with metabolic pathways may contribute to chronic conditions like type 2 diabetes. Studies now suggest that recurrent infections may prime the body for persistent insulin resistance through low-grade inflammation. These insights expand the discussion beyond “can infection raise blood sugar” to whether infection contributes to long-term metabolic disorders. There’s also growing interest in the gut microbiome’s role, as infections and antibiotics can disrupt bacterial populations linked to glucose control. This emerging field holds promise for therapies that address both infectious disease and blood sugar management holistically.

Conclusion: Why It Matters: A Broader View of Metabolic Resilience

Ultimately, the question isn’t just “can infection raise blood sugar,” but rather, what does that tell us about the body’s resilience, adaptability, and vulnerabilities? The interaction between illness and glucose regulation reveals how interconnected our systems truly are. What begins as an immune response to an infection can ripple across metabolic pathways, hormonal balances, and cellular energy dynamics.

For researchers, these observations offer fertile ground for further inquiry into how stress responses shape long-term health outcomes. For clinicians, they emphasize the need for a more integrated approach to managing acute and chronic conditions alike. And for individuals, they provide yet another reason to pay attention to the silent signals the body sends—especially when those signals come in the form of unexpected blood sugar changes during illness.

Whether you’re managing diabetes, supporting a loved one through recovery, or simply trying to understand your own body better, the recognition that illness affects blood sugar adds a crucial layer to your health awareness. It’s not just a matter of controlling a number on a glucometer; it’s about recognizing how the body’s responses to stress, infection, and inflammation are deeply intertwined with overall wellness.

In a world where infectious diseases remain a constant threat and metabolic disorders are on the rise, this understanding could make all the difference.

infection-related glucose spikes, stress-induced hyperglycemia, immune system and blood sugar, illness-driven insulin resistance, acute illness and glucose metabolism, metabolic response to infection, temporary hyperglycemia causes, inflammation and blood sugar, cytokines and insulin resistance, glucose levels during fever;immune response and glucose levels, high blood sugar without diabetes, temporary insulin resistance, viral infection and blood sugar, glucose fluctuations during illness, bacterial infections and hyperglycemia, fever impact on metabolism, dehydration and blood glucose, sickness and sugar regulation, endocrine response to illness

Further Reading:

Handling Diabetes When You’re Sick

Glycemic control in acute illness

Type 2 diabetes and viral infection; cause and effect of disease

Disclaimer: The content published on Better Nutrition News (https://betternutritionnews.com) is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare professional before making any changes to your diet, nutrition, or wellness practices. The opinions expressed by authors and contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect those of Better Nutrition News.

Better Nutrition News and its affiliates make no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the information provided. We disclaim all liability for any loss, injury, or damage resulting from the use or reliance on the content published on this site. External links are provided for reference purposes only and do not imply endorsement.