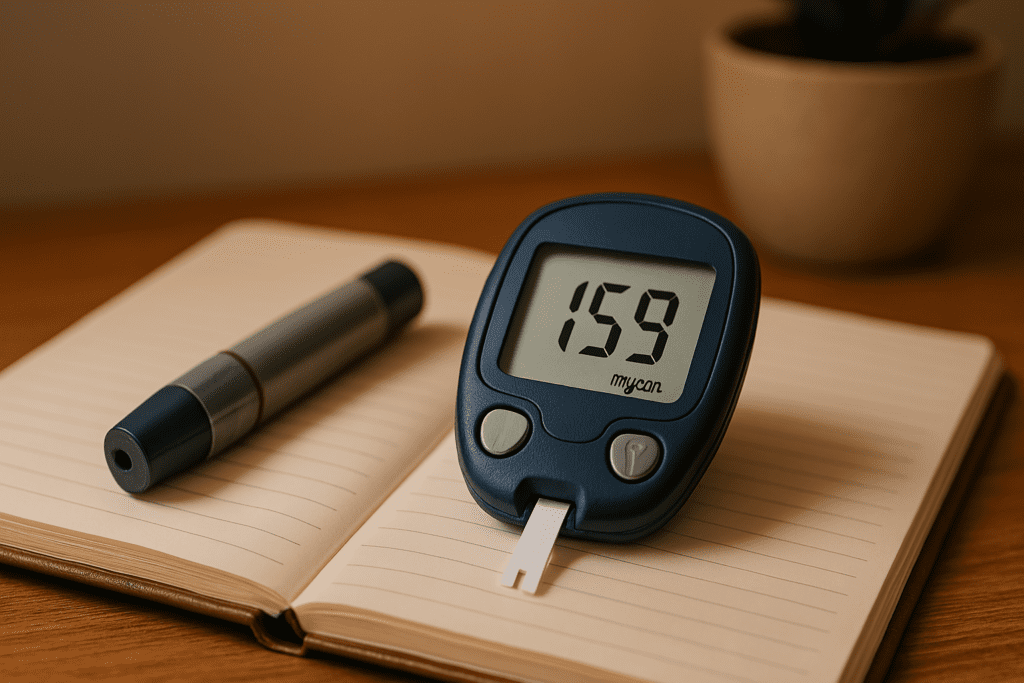

When we eat, our bodies begin a complex and finely tuned physiological process designed to extract, process, and store energy. Central to this system is blood sugar—also known as blood glucose—which rises in response to food intake, particularly meals high in carbohydrates. For most people, this rise is temporary and controlled. But for others, the post-meal spike can be sharp and prolonged, potentially signaling a deeper metabolic imbalance. Understanding what causes high blood sugar after eating, what a 159 blood sugar level means, and how the body reacts with insulin spike symptoms is essential to gaining insight into personal health and long-term metabolic well-being.

You may also like: How Diabetes Affects the Brain: Understanding Brain Fog, Memory Loss, and Mental Confusion from High Blood Sugar

This article takes an in-depth look at the science behind post-meal blood sugar fluctuations. We’ll explore the symptoms that might suggest an abnormal spike, what a high post-meal reading like a blood sugar 200 after eating can imply, and how to interpret specific levels such as a 159 blood sugar result. Equipped with this understanding, readers can better navigate the gray area between “normal” and “concerning” blood glucose responses.

What Happens to Blood Sugar After a Meal?

After eating, particularly a carbohydrate-rich meal, the digestive system breaks down food into simple sugars. These sugars are then absorbed into the bloodstream, causing a rise in blood glucose levels. This spike is a natural, expected part of the digestive process, allowing the body to draw energy from food. However, the rate and magnitude of the increase can vary greatly depending on individual metabolism, insulin sensitivity, physical activity, the meal’s composition, and underlying health conditions.

Typically, the pancreas releases insulin to help shuttle glucose from the blood into cells, where it can be used for energy or stored as glycogen in muscles and the liver. In healthy individuals, this process is smooth and efficient, bringing glucose levels back to baseline within two to three hours. However, if insulin secretion is impaired or the body’s cells are resistant to insulin—a hallmark of insulin resistance—glucose remains elevated longer. This delay can result in high blood sugar after eating, especially when the meal contains refined carbs or sugars with minimal fiber or protein to slow absorption.

While everyone experiences a temporary glucose rise post-meal, the concern arises when these spikes are excessive or frequent. A reading like a 159 blood sugar level one to two hours after eating might not always indicate diabetes, but it could suggest reduced insulin sensitivity, an early sign of metabolic dysregulation. Interpreting these levels in context becomes crucial for long-term health.

High Blood Sugar After Eating: When Is It a Concern?

The definition of “high blood sugar after eating” can be somewhat fluid, depending on whether someone has diabetes, prediabetes, or normal glycemic control. According to the American Diabetes Association, blood sugar levels should ideally remain below 140 mg/dL one to two hours after a meal for most people without diabetes. Readings between 140–199 mg/dL during that window may indicate impaired glucose tolerance or prediabetes, while levels consistently above 200 mg/dL can signal overt diabetes.

However, it’s not just the number but the pattern that matters. A one-off 159 blood sugar level after a particularly large or sugary meal might not be alarming, especially if levels return to baseline within a reasonable timeframe. But repeated elevations like blood sugar 200 after eating—even if they drop later—may contribute to oxidative stress, inflammation, and vascular damage over time.

Emerging research suggests that even in people without diabetes, high postprandial blood glucose spikes can impair endothelial function, raise triglycerides, and promote insulin resistance. Thus, high blood sugar after eating should not be dismissed as benign simply because fasting glucose remains normal. It represents an opportunity to detect early signs of metabolic strain, especially when accompanied by symptoms that suggest poor glucose handling or reactive insulin fluctuations.

Recognizing the Signs of a Blood Sugar Spike

The body often gives subtle but important clues when blood sugar is spiking rapidly. These signs of a blood sugar spike may vary in intensity and presentation depending on individual sensitivity and the magnitude of the glucose rise. Feeling unusually fatigued, drowsy, or mentally foggy after a meal can be an early indicator. Some individuals report headaches, blurred vision, or a sense of jitteriness or restlessness, particularly if the spike is followed by a rapid crash.

Physiologically, a blood sugar spike can temporarily pull fluids from cells, leading to dehydration symptoms such as dry mouth or increased thirst. Frequent urination, although more common in chronic hyperglycemia, can also appear after large spikes. Skin tingling or warmth, lightheadedness, and nausea may also be associated, especially when glucose surges are followed by abrupt insulin-driven drops.

Behavioral signs can include cravings shortly after eating—often for more sugar or starch—as the body attempts to stabilize its glucose supply. This cycle of spikes and dips can feed into patterns of overeating, mood swings, and energy crashes. While occasional fluctuations are part of life, consistent signs of blood sugar spike should prompt further evaluation, especially if they occur even after seemingly balanced meals.

Insulin Spike Symptoms: What They Reveal About Your Metabolism

Insulin spike symptoms often mirror the body’s attempt to rapidly compensate for a sharp glucose rise. When the pancreas responds with an exaggerated insulin release, blood sugar may fall too quickly or too far, leading to reactive hypoglycemia—a drop in blood sugar that occurs shortly after eating. This condition is particularly common in people with insulin resistance or early prediabetes.

Common insulin spike symptoms include shakiness, sweating, anxiety, and a sudden onset of hunger—especially intense cravings for sugar or carbs. These symptoms are a direct response to the body’s attempt to correct the rapid drop in blood sugar by urging more food intake. Some people may also experience irritability, dizziness, palpitations, or even panic attacks as a result of the sharp hormonal shifts accompanying blood sugar and insulin surges.

It’s important to distinguish between general fatigue or meal-induced lethargy and the more specific signs associated with insulin overcompensation. If symptoms occur within one to two hours after eating—especially following a carbohydrate-heavy meal—they may point to dysregulated insulin activity. Over time, frequent insulin spikes can wear down pancreatic function, contribute to insulin resistance, and increase the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes.

Understanding insulin spike symptoms offers a unique window into early metabolic dysfunction. These symptoms can be an early warning that the body is struggling to maintain glucose balance and may require dietary adjustments, increased fiber intake, or closer monitoring of meal timing and macronutrient composition to prevent future issues.

Interpreting a 159 Blood Sugar Level After Eating

When reviewing a 159 blood sugar level one to two hours after a meal, context is everything. For individuals without diabetes, this reading may fall into a borderline or mildly elevated range. The concern increases if this level persists beyond the typical postprandial window or if it follows a modest, low-glycemic meal.

From a clinical perspective, a 159 blood sugar result is not an emergency. However, it does indicate that the body is either producing more insulin than necessary or that cells are not responding effectively to insulin’s signal. If blood sugar remains at or above 159 mg/dL repeatedly, particularly two hours post-meal, it could suggest impaired glucose tolerance.

In contrast, a 159 blood sugar level measured just 30 minutes after eating may not be concerning, as levels naturally peak within 30 to 60 minutes post-ingestion. But if the same level is seen at the two-hour mark, it indicates delayed glucose clearance. This inefficiency can reflect reduced insulin sensitivity, which over time places strain on the pancreas and contributes to chronic hyperglycemia.

Individuals monitoring their glucose through continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) or self-testing should consider both the peak level and the curve—how fast glucose rises and falls. A rapid climb followed by a steep drop could indicate reactive hypoglycemia, while a slow return to baseline may suggest insulin resistance. Interpreting a 159 blood sugar level should thus involve looking at broader trends, lifestyle factors, and overall metabolic context rather than isolated readings alone.

When Post-Meal Levels Reach 200: What a Blood Sugar 200 After Eating Suggests

A blood sugar 200 after eating is generally considered above the normal range, even for the postprandial period. According to diabetes diagnostic criteria, a two-hour reading of 200 mg/dL or higher on an oral glucose tolerance test is one of the markers for diabetes. While a single elevated value may not confirm diagnosis, repeated instances should prompt further investigation.

Experiencing blood sugar 200 after eating regularly may reflect poor insulin response or high insulin resistance. It may also point to an excessive intake of rapidly absorbed carbohydrates—such as refined sugars or processed grains—that overwhelm the body’s regulatory mechanisms. In some cases, stress hormones like cortisol can contribute to elevated post-meal glucose, especially in individuals with adrenal dysfunction or high stress reactivity.

The long-term consequences of repeated blood sugar elevations in the 200 mg/dL range are significant. Persistent high glucose levels damage the delicate lining of blood vessels, promote inflammation, and accelerate the development of atherosclerosis. Over time, this increases the risk for cardiovascular disease, neuropathy, retinopathy, and kidney dysfunction—even in individuals who are not formally diagnosed with diabetes.

For those seeing a blood sugar 200 after eating on occasion, it’s vital to assess the overall dietary pattern, portion sizes, and macronutrient balance. Incorporating more fiber, healthy fats, and lean protein can blunt the post-meal rise. Physical activity shortly after eating—such as a 10-minute walk—can also significantly reduce postprandial spikes and improve insulin sensitivity.

How Diet, Lifestyle, and Metabolism Shape Glucose Responses

Individual responses to food are shaped by a complex interplay of factors including genetics, microbiome composition, sleep quality, physical activity, and hormonal balance. Some people may see a 159 blood sugar level after a bowl of oatmeal, while others might have a more muted response. This interindividual variability highlights why personalized nutrition and glucose monitoring can be more informative than generalized dietary advice.

Insulin sensitivity is one of the most critical variables. When cells are responsive to insulin, even carbohydrate-rich meals are cleared efficiently. In contrast, insulin-resistant individuals will see a slower decline in glucose levels post-meal, leading to prolonged elevations. Improving insulin sensitivity through resistance training, aerobic activity, and intermittent fasting strategies has been shown to enhance glucose handling over time.

Sleep plays a less obvious but vital role. Short sleep duration, poor sleep quality, or circadian rhythm disruption can impair insulin function and raise postprandial glucose levels. Similarly, stress increases cortisol, which can blunt insulin activity and promote glucose release from the liver. Managing these lifestyle elements is crucial for moderating high blood sugar after eating.

Finally, the composition and timing of meals matter significantly. High-glycemic index foods cause rapid spikes, while meals balanced with fiber, protein, and fat result in slower, more gradual glucose increases. Timing meals earlier in the day, when insulin sensitivity is higher, can also help reduce blood sugar excursions.

Metabolic Red Flags and When to Seek Medical Insight

Persistent signs of blood sugar spike, such as fatigue after eating, frequent cravings, or shakiness, are worth investigating—especially when accompanied by elevated readings like a 159 blood sugar level. These symptoms may point to early insulin resistance or a condition known as impaired glucose tolerance, which often precedes the development of Type 2 diabetes.

If symptoms of reactive hypoglycemia—like dizziness or heart palpitations—occur frequently after meals, they may indicate erratic insulin release patterns. Similarly, a consistent blood sugar 200 after eating suggests a reduced ability to process carbohydrates efficiently and may warrant diagnostic testing, including an A1C test or glucose tolerance assessment.

Medical evaluation is also important for ruling out less common causes of abnormal glucose responses, such as pancreatic disorders, hormonal imbalances, or medication effects. For individuals with autoimmune conditions, thyroid dysfunction, or a family history of diabetes, monitoring blood sugar trends becomes even more critical.

Even in the absence of a formal diagnosis, ongoing post-meal spikes can signal metabolic inflexibility—an early indicator that the body is struggling to maintain equilibrium. Addressing these shifts early through lifestyle changes, medical consultation, and individualized monitoring offers the best chance to restore balance and avoid progression to chronic disease.

Frequently Asked Questions About Blood Sugar Spikes and Insulin Reactions After Eating

1. Why do some people experience high blood sugar after eating even with a healthy diet?

A high blood sugar after eating can still occur in individuals following a seemingly healthy diet due to several factors such as hidden sugars, delayed insulin response, or reduced insulin sensitivity. Even whole foods like brown rice or sweet potatoes, while nutritious, can cause a spike if consumed in large portions or without protein or fat to slow glucose absorption. Some people also have a blunted first-phase insulin response, leading to higher post-meal readings. Additionally, stress or poor sleep the night before can impair glucose metabolism, contributing to a high blood sugar after eating. Monitoring patterns over time helps differentiate isolated events from chronic glucose regulation issues.

2. What are less obvious signs of a blood sugar spike that people often overlook?

While fatigue and thirst are commonly known, subtle signs of blood sugar spike may include blurry vision, lightheadedness, restlessness, or even a sensation of warmth or flushing. Cognitive fog, sudden irritability, and compulsive eating urges can also suggest that your glucose levels are surging. These symptoms can appear even if blood sugar doesn’t reach diabetic thresholds. For example, someone with a 159 blood sugar level might not feel “sick” but still experience mental cloudiness or sudden hunger. Being aware of these less discussed signs of a blood sugar spike can improve early detection and help fine-tune meal composition or timing.

3. Can an insulin spike cause symptoms even if blood sugar is not dramatically high?

Yes, insulin spike symptoms can arise even when blood glucose levels are relatively moderate. A rapid or excessive insulin release—often triggered by high glycemic foods—can cause a subsequent crash in blood sugar, resulting in shakiness, sweating, anxiety, and weakness. These insulin spike symptoms may occur after a sharp rise and fall in blood sugar, such as when a person goes from a blood sugar 200 after eating down to under 90 mg/dL within an hour. This fluctuation stresses the body and creates symptoms even in non-diabetic individuals. Understanding how quickly your glucose falls can be just as important as knowing how high it climbs.

4. How concerning is a 159 blood sugar level one hour after eating?

A 159 blood sugar level one hour post-meal can be a borderline indicator of impaired glucose tolerance, especially if it remains elevated beyond two hours. While many clinicians view a 159 blood sugar level as mild, frequent readings at this level should not be ignored. Over time, recurrent spikes to 159 may contribute to insulin resistance and vascular stress. Factors like age, BMI, and activity level post-meal influence how concerning a 159 blood sugar reading is. To assess the full picture, it’s useful to check blood glucose at multiple intervals and consider continuous glucose monitoring if patterns persist.

5. What does it mean if your blood sugar reaches 200 after eating?

A blood sugar 200 after eating typically signals that your body is struggling with glucose regulation, especially if it doesn’t drop significantly within two hours. While a temporary blood sugar 200 after eating can result from a high-carb or sugary meal, it may also reflect insulin resistance or pancreatic inefficiency. If this occurs frequently, it increases the risk of microvascular complications and progression toward type 2 diabetes. Addressing a blood sugar 200 after eating involves more than cutting carbs; it also means improving sleep, reducing stress, increasing muscle mass, and spacing meals appropriately. Glucose curves tell a richer story than single readings alone.

6. What strategies help prevent high blood sugar after eating large meals?

Preventing high blood sugar after eating involves meal sequencing, timing, and composition. Starting meals with non-starchy vegetables or protein can blunt glucose absorption, as can slowing your eating pace. Incorporating post-meal physical activity—like a 10-minute walk—dramatically lowers the likelihood of high blood sugar after eating, even when the meal is carb-rich. It’s also essential to evaluate portion sizes of “healthy” starches, which can still lead to a blood sugar 200 after eating if not properly balanced. Using a continuous glucose monitor can help fine-tune strategies by revealing exactly how different foods affect your body.

7. Are there psychological effects associated with recurring blood sugar spikes?

Repeated signs of blood sugar spike are not just physical—they can have a psychological toll as well. Sudden shifts in glucose levels may lead to mood instability, poor impulse control, and even depressive symptoms over time. People often report “brain fog” or irritability when blood sugar fluctuates rapidly, especially after hitting levels like a 159 blood sugar or higher. The repeated stress of self-monitoring and fear of complications may also contribute to anxiety or obsessive food behaviors. Psychological support, cognitive-behavioral tools, and blood sugar stabilization plans can help mitigate these emotional burdens.

8. Can exercise trigger or reduce insulin spike symptoms after meals?

Exercise plays a dual role in managing insulin spike symptoms. Light physical activity after meals—like walking—can greatly reduce glucose and insulin peaks by increasing cellular uptake of glucose without needing additional insulin. However, intense workouts, especially in a fasted state, can temporarily elevate blood sugar due to adrenaline, potentially triggering signs of blood sugar spike. Balancing the timing, intensity, and duration of exercise is key. For instance, someone with a 159 blood sugar level after eating might benefit from low-intensity movement more than high-impact cardio immediately post-meal. Personalized exercise timing can stabilize postprandial responses effectively.

9. How can people interpret a consistent 159 blood sugar reading after meals?

A consistent 159 blood sugar level post-meal suggests an early warning sign of metabolic imbalance, especially if it’s a recurring trend. While not immediately dangerous, a steady 159 blood sugar level is above optimal for long-term vascular and neurological health. This pattern may indicate that your body is producing enough insulin, but your cells aren’t responding effectively—also known as early-stage insulin resistance. Monitoring whether your blood sugar returns to baseline within 2–3 hours is crucial. Making dietary adjustments or using targeted supplements like berberine under medical guidance can support glucose metabolism in these cases.

10. How does the timing of meals influence blood sugar spikes and insulin reactions?

Meal timing has a significant effect on signs of blood sugar spike and insulin efficiency. Eating late at night or skipping breakfast often results in exaggerated glucose and insulin responses at subsequent meals. For example, someone might see a blood sugar 200 after eating dinner if they had irregular food intake during the day. Circadian rhythms also influence insulin sensitivity—glucose control is often better in the morning than evening. Strategically spacing meals and avoiding large evening portions can help maintain post-meal levels closer to a 159 blood sugar or below. Aligning meals with your biological clock supports both short- and long-term metabolic health.

Closing the Loop: Why Monitoring Post-Meal Glucose Is a Vital Health Insight

Understanding how the body responds to food is more than a curiosity—it’s a powerful diagnostic and preventive tool. High blood sugar after eating, especially when readings like 159 blood sugar or blood sugar 200 after eating occur frequently, reveals much about insulin efficiency, metabolic resilience, and long-term health trajectory. These measurements, when paired with awareness of insulin spike symptoms and the signs of blood sugar spike, empower individuals to take control of their metabolic health before more serious conditions develop.

Ultimately, a 159 blood sugar level after a meal might not mean you have diabetes—but it does offer a valuable signal. It’s an invitation to investigate further, to consider the roles of food, movement, stress, and sleep in shaping metabolic responses. By listening to the body’s signals, responding to symptoms with intention, and seeking professional guidance when needed, we can create a more resilient, informed, and sustainable approach to health.

high glycemic meals and metabolism, postprandial glucose effects, signs of insulin resistance, reactive hypoglycemia symptoms, blood sugar regulation after eating, metabolic flexibility and diet, continuous glucose monitoring benefits, non-diabetic hyperglycemia insights, insulin sensitivity improvement, cardiovascular effects of blood sugar spikes, interpreting CGM data, glucose metabolism and exercise, personalized nutrition strategies, early signs of type 2 diabetes, fiber and blood sugar control, stress and postprandial glucose, insulin and satiety signals, understanding glycemic index, role of protein in glucose balance, sugar cravings and metabolism

Further Reading:

What to know about blood sugar spikes in diabetes

Those bothersome blood sugar spikes after meals…

Food Order Has a Significant Impact on Postprandial Glucose and Insulin Levels

Disclaimer: The content published on Better Nutrition News (https://betternutritionnews.com) is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare professional before making any changes to your diet, nutrition, or wellness practices. The opinions expressed by authors and contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect those of Better Nutrition News.

Better Nutrition News and its affiliates make no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the information provided. We disclaim all liability for any loss, injury, or damage resulting from the use or reliance on the content published on this site. External links are provided for reference purposes only and do not imply endorsement.