Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is widely recognized for its impact on memory, reasoning, and behavior, but recent research has begun to shed light on another area of concern that is gaining increasing attention: the eyes. While memory loss remains the most talked-about symptom, subtle and sometimes strange changes in vision may precede the cognitive impairments commonly associated with this neurodegenerative disease. These early visual alterations are now being studied not just as symptoms, but as potential early indicators of Alzheimer’s itself. Understanding these early Alzheimer vision problems could offer a critical window into earlier diagnosis, better monitoring, and more effective interventions.

You may also like: How to Stop Cognitive Decline: Science-Backed Steps for Prevention and Brain Longevity

Visual perception is often taken for granted, assumed to be the result of clear eyes and healthy retinas. However, vision is also fundamentally a brain function. The eyes collect data, but it is the brain—especially areas like the occipital lobe, parietal cortex, and visual association areas—that interpret that data and transform it into the images we consciously perceive. In Alzheimer’s disease, these brain regions may begin to malfunction well before memory loss becomes apparent. This dysfunction can lead to visual symptoms that seem odd, inconsistent, or unexplained by typical eye exams. Some people might begin to bump into furniture, misjudge distances, or struggle with reading and depth perception, despite otherwise good eye health. These signs may appear long before a formal diagnosis is made.

In fact, for some individuals, the first noticeable clue that something might be wrong cognitively comes not through forgetfulness, but through weird vision problems. Early Alzheimer vision problems often manifest subtly, making them easy to overlook or misattribute to normal aging or unrelated eye issues like cataracts or presbyopia. Yet when these changes are examined in conjunction with other risk factors or mild cognitive concerns, they can paint a compelling picture of what is happening deep within the brain. Moreover, advancements in eye imaging and visual assessments are creating promising new tools for early Alzheimer detection—non-invasive, accessible, and surprisingly informative.

This article explores how and why vision changes may occur in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, what symptoms to watch for, and how both patients and clinicians can use this information to support earlier diagnosis and care. From research insights to clinical implications, we’ll uncover what these visual signs reveal about the brain’s cognitive decline, and how they might transform the way we recognize and respond to dementia. By understanding the links between eye health and neurodegeneration, we can become more proactive and informed in identifying Alzheimer’s before it fully takes hold.

The Neurology of Vision: Why Alzheimer’s Affects the Eyes

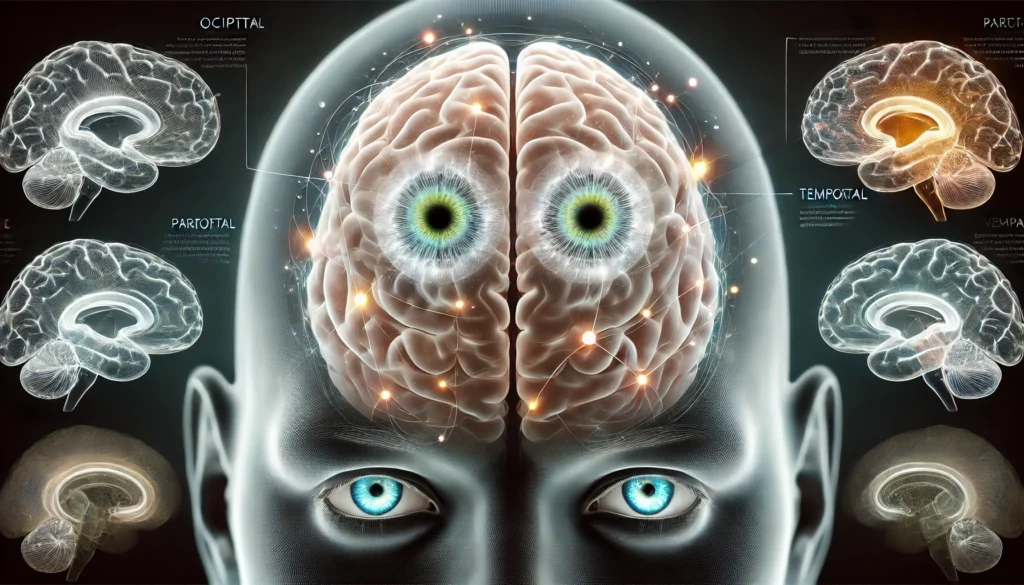

To understand early Alzheimer vision problems, it is essential to recognize the complex relationship between the eyes and the brain. Vision is not just a matter of the retina and the optic nerve; it involves a sophisticated network of neural pathways and cortical processing centers. Visual information travels from the retina through the optic nerve to the brain’s visual cortex, where it is interpreted, contextualized, and integrated with memories and spatial awareness. In Alzheimer’s disease, the neural degeneration that affects memory and behavior also impairs this intricate system of visual processing.

The occipital lobe, located at the back of the brain, is primarily responsible for interpreting visual stimuli. But Alzheimer’s doesn’t limit its damage to this area alone. It affects the parietal lobe, which helps with spatial orientation and movement coordination, and the temporal lobe, which processes complex visual input like recognizing faces or reading. When Alzheimer-related plaques and tangles accumulate in these areas, the processing of visual information becomes disrupted.

One major contributor to Alzheimer vision problems is the degradation of the posterior cortical region—a part of the brain that combines visual input with spatial and conceptual understanding. This can lead to symptoms like visual agnosia (difficulty recognizing familiar objects or faces), optic ataxia (misjudging the location of objects), and difficulties with depth perception or contrast sensitivity. These changes can be deeply unsettling for patients and confusing for loved ones, as they are often mistaken for clumsiness, carelessness, or declining vision unrelated to brain function.

Importantly, these impairments are not necessarily detectable with standard vision tests. A person might have 20/20 vision but still struggle to interpret what they see. This disconnect between physical eye health and perceptual ability highlights why traditional eye exams may miss early Alzheimer vision problems entirely. More specialized assessments, including contrast sensitivity tests, color perception evaluations, and retinal imaging, are becoming increasingly relevant in this context.

Weird Vision Problems That Could Signal Early Alzheimer’s

In recent years, anecdotal accounts and clinical case studies have converged on a recurring pattern: patients developing strange or inconsistent vision problems well before showing obvious memory loss. These weird vision problems in early Alzheimer cases can be diverse, ranging from minor frustrations to life-altering challenges.

One of the most frequently reported early visual symptoms is trouble with spatial orientation. People may start bumping into furniture, misjudging where doorways are, or having trouble navigating stairs. These issues are often attributed to poor depth perception, but in Alzheimer’s, they are linked to a disruption in spatial processing in the brain. The person might see objects clearly, but their brain misinterprets the space between those objects or their location in the environment.

Other unusual vision problems include difficulty recognizing familiar faces (prosopagnosia), problems following visual scenes (such as reading a page or watching a movie), or experiencing visual illusions, like mistaking patterns in wallpaper for faces or objects. Some individuals may also develop an increased sensitivity to light or glare, making it hard to drive or navigate in brightly lit or dim environments. These symptoms can appear disjointed and may not initially be connected to cognitive decline, which can delay diagnosis.

In more advanced cases of early Alzheimer vision problems, individuals may develop Balint’s syndrome—a rare neurodegenerative condition characterized by a cluster of visual symptoms including simultanagnosia (inability to perceive more than one object at a time), ocular apraxia (difficulty moving the eyes intentionally), and optic ataxia. While this syndrome is not always present, its hallmark features demonstrate the extent to which Alzheimer’s can impair visual coordination and awareness.

Notably, weird vision problems in early Alzheimer are often brushed aside by general practitioners or attributed to eye strain, aging, or stress. Yet when considered in the broader context of cognitive health, these early visual disruptions can provide critical insight into the disease’s progression and should not be dismissed.

How the Eyes Reveal the Brain’s Health

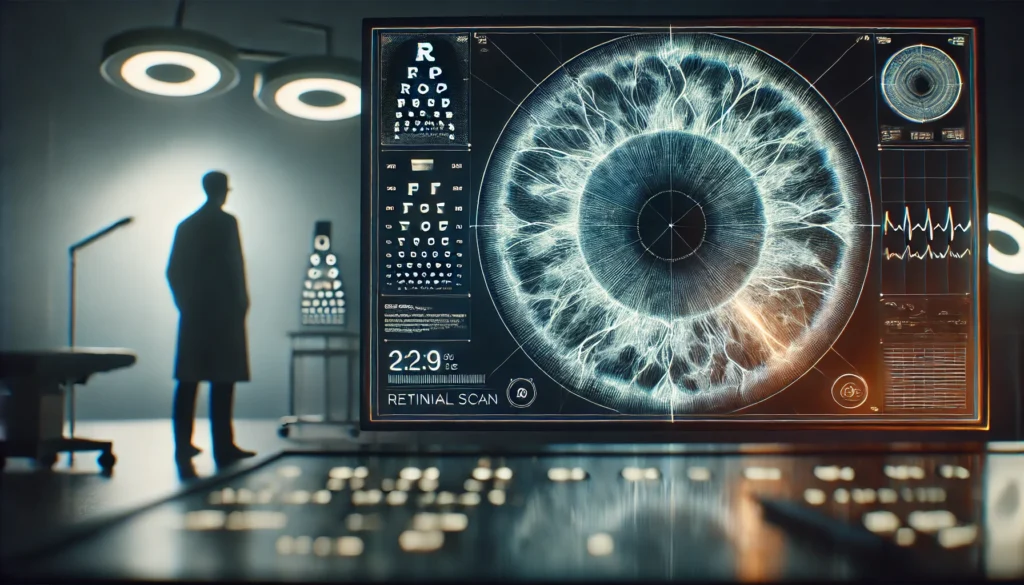

Recent advancements in ophthalmic imaging and neurological diagnostics are bridging the gap between eye health and brain health. Researchers have discovered that the retina—technically an extension of the central nervous system—can serve as a window into brain pathology, including that caused by Alzheimer’s. Changes in the retina’s structure, blood flow, and neuronal layers may correlate with the presence of amyloid plaques and tau protein tangles found in the brain.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a non-invasive imaging technique that has shown promise in identifying early Alzheimer vision problems by detecting thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer. This thinning mirrors the neuronal loss occurring in the brain and may serve as a biomarker for early cognitive decline. Studies have found that individuals with mild cognitive impairment or early Alzheimer’s often show measurable retinal changes, even before memory symptoms arise.

Another fascinating development is the use of fluorescent imaging to detect beta-amyloid deposits in the retina. These deposits are hallmark features of Alzheimer’s disease and were once only visible through post-mortem brain analysis or advanced neuroimaging. Now, researchers are working on retinal scanning tools that could detect these deposits years before clinical symptoms become apparent, offering a powerful new method for screening at-risk populations.

In addition to imaging, certain functional vision tests are gaining traction. These tests assess contrast sensitivity, color vision, visual motion perception, and visual field awareness—all of which may be subtly impaired in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. By evaluating how the brain processes visual stimuli, clinicians can gather crucial clues about cognitive status without the need for more invasive or expensive testing.

These emerging diagnostic tools not only support earlier and more accurate detection but also empower patients and caregivers by validating their experiences. When someone reports weird vision problems in early Alzheimer, having objective tests to back up those concerns can make a profound difference in receiving the right diagnosis and care.

Recognizing the Early Signs of Dementia in the Eyes

Among the most fascinating aspects of early Alzheimer diagnosis is the idea that the eyes might literally look different. While this concept is still being explored, some researchers and clinicians have noted that changes in eye appearance—such as a glassy or distant look, altered blinking patterns, or loss of expressiveness—may occur subtly in the early stages of dementia. These changes might be dismissed as subjective, but mounting anecdotal evidence and preliminary studies suggest they could serve as another red flag in identifying cognitive decline.

In many cases, caregivers and close family members notice these early signs of dementia when the eyes look different—not just in vision but in how the individual uses eye contact, focuses on people or objects, or responds to facial cues. This decline in visual engagement may be due to deterioration in brain regions responsible for processing facial expressions, eye contact, and social cues. Such changes can affect emotional connection, leading to misunderstandings or perceived withdrawal from social interaction.

For example, a person might seem to stare blankly or avoid eye contact altogether, which could be misinterpreted as disinterest or depression. In reality, their brain may be struggling to process the complex visual and emotional information conveyed through another person’s face. These eye-related symptoms can have a profound impact on relationships and communication, particularly if their cause is not understood.

Recognizing these early signs of dementia when the eyes look different is crucial not only for early diagnosis but also for improving empathy and support. When caregivers understand that these changes are neurological rather than behavioral, they are better equipped to respond with compassion and appropriate intervention. This understanding also reinforces the importance of comprehensive assessments that include not just memory tests but visual and behavioral evaluations as well.

How Vision Changes Impact Daily Life and Safety

Early Alzheimer vision problems can have wide-ranging effects on daily life, even before memory loss becomes severe. Simple tasks like reading, driving, cooking, or walking through a familiar room may suddenly become challenging or even dangerous. For example, a person who once read books avidly may now struggle to follow lines of text or confuse letters. Someone who used to drive confidently may begin missing stop signs, confusing left and right, or reacting slowly to obstacles on the road.

These impairments stem from a breakdown in the brain’s ability to coordinate vision with movement, decision-making, and spatial awareness. As a result, individuals may experience disorientation in new environments, increased risk of falls, or difficulty with tasks that require fine visual-motor skills. They might hesitate at curbs, avoid going outdoors, or withdraw from activities that once brought them joy. This functional decline can be mistaken for depression or apathy, when in reality, it’s rooted in visual-cognitive difficulties.

Beyond physical challenges, early Alzheimer vision problems can also impact emotional well-being. Many people report feeling frustrated, embarrassed, or even fearful when their vision doesn’t behave as expected. They may stop attending social events, avoid hobbies, or withdraw from conversations that require visual engagement. These changes, if not properly addressed, can lead to a worsening cycle of isolation and cognitive decline.

Caregivers should be alert to these vision-related struggles and consider how environmental adaptations—such as improved lighting, contrasting colors, simplified layouts, and assistive devices—can reduce stress and increase safety. Occupational therapists and neuro-ophthalmologists can offer tailored strategies to help individuals adapt to visual impairments without losing independence or quality of life.

Clinical Assessment and Diagnosis: Looking Beyond Memory

For decades, Alzheimer’s diagnosis focused primarily on memory loss and language deficits, but this narrow approach may delay recognition of other early symptoms—especially those related to vision. Today, clinicians are beginning to incorporate a broader range of cognitive and sensory evaluations into their diagnostic process, acknowledging the important role of vision in identifying early Alzheimer’s.

A comprehensive assessment for suspected Alzheimer’s should now include a detailed review of visual symptoms, especially if they are unusual or difficult to explain through traditional eye health. Patients should be asked about difficulties with spatial navigation, reading, facial recognition, depth perception, and other specific visual tasks. These questions can reveal impairments that might otherwise go unnoticed during a routine exam.

Neuropsychological testing can provide a more in-depth look at visual-spatial processing, visual memory, and perceptual reasoning. These tests measure how well a person interprets and responds to visual information, helping to identify specific brain areas that may be affected by Alzheimer’s pathology. In some cases, these tests are more sensitive than memory exams in detecting early disease.

Imaging studies such as MRI or PET scans can further clarify whether the brain regions involved in visual processing show signs of atrophy or metabolic dysfunction. When combined with OCT or other retinal imaging, these tools offer a multidimensional view of how Alzheimer’s is affecting both the brain and eyes. This integrated approach can lead to earlier and more accurate diagnoses, which in turn opens the door to better care and planning.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the most common vision problems associated with early Alzheimer’s?

The most common vision problems in early Alzheimer’s include difficulty with depth perception, trouble reading, problems recognizing faces, and visual misinterpretations. These issues occur even when the eyes themselves are healthy, indicating the problem lies in the brain’s visual processing centers. Spatial disorientation is another frequently reported symptom, leading to bumping into objects or getting lost in familiar places.

2. How do weird vision problems in early Alzheimer differ from typical aging-related vision issues?

Typical aging-related vision problems, such as presbyopia or cataracts, affect the eyes’ physical structures and are usually correctable with glasses or surgery. In contrast, weird vision problems in early Alzheimer arise from neurological damage and involve difficulties interpreting visual information. These symptoms may include visual hallucinations, inability to judge distances, or recognizing objects incorrectly despite having normal eye exams.

3. Can eye doctors detect Alzheimer’s during a routine eye exam?

Most routine eye exams do not include assessments for neurological processing, so they may not detect Alzheimer’s-related vision changes. However, some eye doctors who use advanced imaging like OCT or who are trained in neuro-ophthalmology may notice signs that warrant further investigation. As research progresses, more eye care professionals may play a role in early Alzheimer detection.

4. Are there any eye tests specifically designed to detect Alzheimer’s?

Yes, emerging technologies such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) and retinal imaging techniques are being developed to detect signs of Alzheimer’s in the eyes. These tests can measure retinal thinning, reduced blood flow, or even amyloid plaque deposits in the retina. Functional vision tests that evaluate contrast sensitivity, motion detection, and facial recognition are also being explored for their diagnostic potential.

5. Why do some people with Alzheimer’s have difficulty recognizing faces?

Face recognition relies on specific areas of the brain, particularly in the temporal and occipital lobes. In Alzheimer’s disease, these areas can become damaged, leading to a condition known as prosopagnosia. This makes it difficult for individuals to identify even familiar people, which can be distressing and socially isolating. The issue is not with seeing the face, but with processing and remembering it.

6. How early can vision changes begin in Alzheimer’s?

Vision changes can begin years before memory problems become noticeable. In some cases, subtle visual impairments are among the first signs of cognitive decline. Because these symptoms are often attributed to normal aging or minor eye issues, they are frequently overlooked. Early detection of vision changes, especially when paired with other cognitive concerns, can lead to a timelier Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

7. What are the early signs of dementia when eyes look different?

When the eyes look different in early dementia, it often refers to changes in how individuals use their eyes—such as reduced eye contact, a blank or distant gaze, altered blinking, or unusual facial expressiveness. These changes may reflect deeper impairments in how the brain processes social cues, emotional signals, and visual information, and are sometimes noticed by family members before other symptoms appear.

8. Can Alzheimer’s patients experience visual hallucinations?

Yes, some Alzheimer’s patients may experience visual hallucinations, especially in the later stages or if they have overlapping conditions like Lewy body dementia. These hallucinations can include seeing people, animals, or patterns that aren’t there. While not all individuals with Alzheimer’s will have hallucinations, their presence can be a sign of more advanced cognitive impairment and should be evaluated by a doctor.

9. How do visual symptoms affect the quality of life in early Alzheimer’s?

Visual symptoms can significantly impact quality of life by making everyday tasks more difficult and stressful. Activities like reading, driving, cooking, or recognizing loved ones may become frustrating or even dangerous. These impairments often lead to withdrawal from social situations, increased dependence on caregivers, and heightened anxiety or depression. Addressing visual symptoms early can improve safety and emotional well-being.

10. Should someone with early Alzheimer vision problems stop driving?

If vision problems interfere with spatial awareness, reaction time, or judgment, it may be unsafe for the person to drive. A comprehensive evaluation—including a vision assessment and cognitive testing—can help determine driving fitness. In many cases, occupational therapists or driving specialists can offer guidance and alternative transportation solutions to support continued independence while prioritizing safety.

Conclusion

Early Alzheimer vision problems offer an underrecognized yet potentially transformative path to earlier detection and intervention. While memory loss and confusion have long dominated the conversation around dementia, strange or subtle vision changes may precede these hallmark symptoms and provide crucial insight into what is happening in the brain. From trouble with spatial awareness to difficulty reading or recognizing faces, these visual symptoms reflect a deeper disruption in neurological processing—one that can occur years before traditional cognitive tests reveal a problem.

Weird vision problems in early Alzheimer often go unreported or are misunderstood, but growing research is helping to bring these symptoms into the spotlight. Advances in retinal imaging, visual assessments, and neurological understanding are creating new possibilities for diagnosis that are less invasive and more accessible. Recognizing the early signs of dementia when the eyes look different, both visually and behaviorally, can also empower caregivers to seek support sooner and ensure that patients receive the compassionate, informed care they deserve.

Ultimately, vision changes are not just peripheral concerns in the Alzheimer’s journey—they are deeply tied to the brain’s integrity and function. By paying attention to how a person sees, interprets, and responds to the world around them, we can open a powerful new chapter in the early recognition and personalized treatment of this complex disease. If you or someone you love is experiencing unexplained visual challenges, don’t ignore them. They may be the first signs of something deeper—and the first chance to make a meaningful difference.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

Facial Signs of Dementia: Does Dementia Change Your Face and Affect the Way You Smile?