Introduction

Memory is the cornerstone of our identity, connecting us to our past, anchoring us in the present, and guiding our decisions for the future. When memory begins to falter, it not only affects our ability to recall facts or recognize faces but also undermines the very essence of who we are. A memory disorder is not merely forgetfulness; it can be a life-altering condition that impacts daily functioning, personal relationships, and emotional well-being. Even more complex is the intersection between memory impairment and mental health, a domain that reveals how mental disorder memory loss can obscure diagnosis, delay treatment, and challenge recovery. As science continues to unravel the intricacies of brain function, we are beginning to understand the nuanced distinctions between organic memory disorders and memory loss associated with psychological conditions. This article dives deep into these dimensions, exploring definitions, root causes, symptom patterns, diagnostic challenges, and emerging treatments, all while making clear how intertwined cognition and mental health truly are.

You may also like: How to Stop Cognitive Decline: Science-Backed Steps for Prevention and Brain Longevity

Defining Memory Disorders and Their Scope

A memory disorder refers to a condition in which an individual experiences significant, often progressive, difficulties in remembering, storing, or recalling information. These disorders can be congenital, acquired through injury, or develop due to neurodegenerative disease. While everyone occasionally forgets where they left their keys or the name of a new acquaintance, individuals with a memory disorder experience consistent, disruptive memory failures that impair everyday life. Unlike typical age-related forgetfulness, these memory disturbances may signify a deeper neurological issue, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, or traumatic brain injury.

Memory disorders can be categorized based on the type of memory affected: short-term, long-term, procedural, or episodic. Each type of memory is governed by distinct neural pathways and brain structures, meaning that the cause of dysfunction often gives clues as to which type is most affected. For example, hippocampal damage typically impairs the formation of new long-term memories, while frontal lobe damage may affect the strategic recall of stored information.

In clinical contexts, memory disorders often present alongside other cognitive impairments, such as difficulty concentrating, confusion, or language deficits. They may appear gradually or suddenly, depending on the underlying cause. Importantly, early intervention can sometimes reverse or stabilize these symptoms, making prompt diagnosis crucial.

Mental Health and Memory: The Overlap

When considering mental disorder memory loss, it’s vital to distinguish between memory loss that is the result of a psychiatric condition and memory deficits that mimic or coexist with mental illness. Mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia frequently involve changes in cognitive function. In many cases, memory impairment is one of the first symptoms noted by patients or caregivers.

In depressive disorders, for instance, memory loss may present as poor recall, especially for recent events or conversations. This isn’t due to damage in the brain’s memory centers, but rather a decline in attention, motivation, and executive functioning. A person struggling with depression may have difficulty encoding new memories because their brain is preoccupied with rumination and emotional dysregulation.

Schizophrenia, a severe psychiatric illness, is often accompanied by deficits in working memory and episodic recall. The cause here is more structural, involving abnormalities in prefrontal cortex function and dopamine regulation. Similarly, individuals with bipolar disorder may experience cognitive deficits that fluctuate with mood states, leading to temporary or chronic memory problems.

Understanding the cognitive burden of psychiatric illness is essential, as patients with mental disorder memory loss may be misdiagnosed with dementia or other organic brain syndromes, delaying effective treatment. Neuropsychological assessments can help distinguish between the two by evaluating specific domains of cognition, emotion, and behavior.

Causes of Memory Disorders

The etiology of a memory disorder is as diverse as the brain itself. Common causes include neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, vascular issues such as stroke, infections like encephalitis, autoimmune diseases such as lupus, traumatic brain injury, and substance abuse. Each of these causes has unique pathways through which memory is affected, and treatment often depends on the precise source of damage.

Alzheimer’s disease, the most prevalent memory disorder, results in the gradual breakdown of neurons in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex. As the disease progresses, individuals lose the ability to form new memories and eventually forget previously established knowledge and skills.

Vascular dementia, by contrast, stems from reduced blood flow to the brain due to stroke or small vessel disease. This form of memory disorder often progresses in a stepwise fashion, with sudden declines linked to additional vascular events.

Trauma is another major contributor to memory dysfunction. Concussions, car accidents, and falls can result in both immediate and long-term cognitive deficits. Traumatic brain injuries may disrupt neural connections vital for memory consolidation and recall, and in severe cases, they can lead to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

Substance abuse, particularly chronic alcohol use, can result in Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, a devastating condition that includes both anterograde and retrograde amnesia. Similarly, long-term use of benzodiazepines and other psychoactive drugs may contribute to memory loss, especially in older adults.

Autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis or lupus can cause inflammatory damage to the brain, which in turn affects memory and other cognitive functions. Viral infections such as herpes simplex encephalitis can directly damage memory-processing regions of the brain, resulting in acute and severe memory deficits.

Mental Disorders as Indirect Causes of Memory Impairment

Unlike primary memory disorders, psychiatric illnesses often impair memory indirectly. In the case of depression, reduced serotonin and dopamine levels affect the brain’s ability to encode and retrieve information. People in depressive episodes often report feeling mentally “foggy” or unable to remember basic tasks or details. This cognitive symptom can worsen the emotional distress of the individual, reinforcing feelings of inadequacy and hopelessness.

Anxiety disorders can lead to memory lapses due to the brain’s hyperarousal state. Constant stress activates the amygdala while suppressing the hippocampus, creating a neurological environment that favors threat detection over memory consolidation. Individuals with chronic anxiety may remember negative experiences more vividly while forgetting benign or positive ones.

In bipolar disorder, mania can produce racing thoughts and impulsivity that interfere with focused attention, making it difficult to encode memories. During depressive episodes, similar mechanisms to those in unipolar depression are at play. Over time, the cumulative effect of mood swings and psychotropic medications may contribute to structural brain changes and long-term memory issues.

Schizophrenia stands out among mental disorders due to the profound impact it has on cognitive function. Working memory, long-term recall, and executive function are all impaired. These deficits are believed to be core features of the illness and not just side effects of medication or environmental stressors. The level of cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia often correlates with functional impairment and quality of life.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) also plays a role in mental disorder memory loss, as individuals may either block out traumatic memories or experience intrusive, unwanted recollections. Dissociation, a coping mechanism for trauma, can further fracture memory, leaving individuals with gaps in autobiographical recall.

Diagnosing Memory Disorders and Memory Loss Linked to Mental Illness

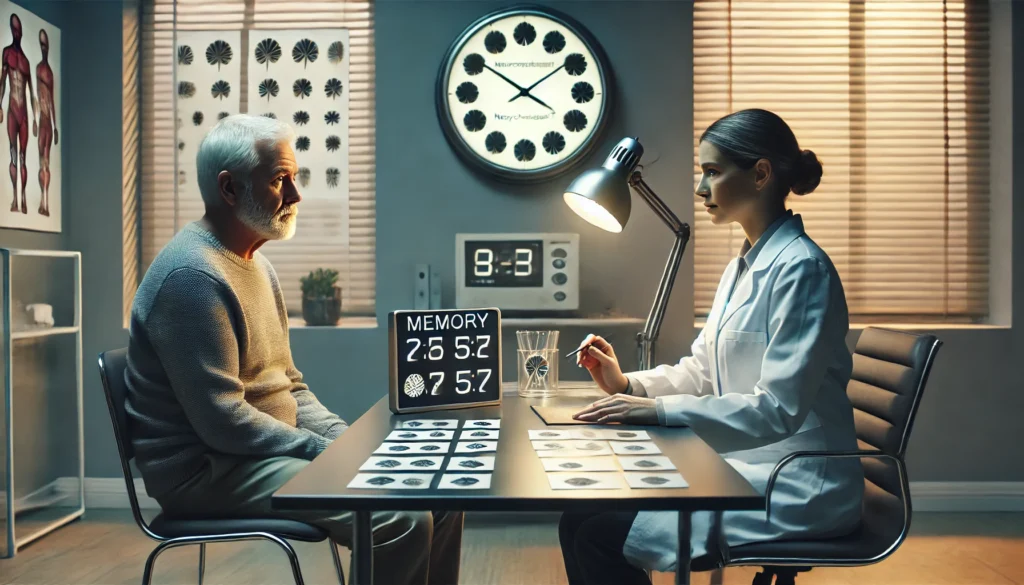

Diagnosis begins with a comprehensive history and physical examination. Medical providers assess symptom patterns, onset, duration, and severity. They also consider personal and family history, substance use, and psychological factors. Cognitive screening tools such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) provide a baseline for memory function.

When mental disorder memory loss is suspected, a psychiatric evaluation becomes crucial. This includes assessment for depression, anxiety, psychosis, and other psychological conditions. Neuroimaging studies such as MRI or CT scans may reveal structural abnormalities, including hippocampal atrophy or lesions. In some cases, PET scans can highlight reduced glucose metabolism in specific brain regions associated with memory.

Neuropsychological testing remains the gold standard for differential diagnosis. These in-depth assessments evaluate memory, attention, language, and executive functioning through standardized tasks. They can distinguish between memory loss due to a primary neurological condition and cognitive deficits secondary to psychiatric illness.

Laboratory tests may be employed to rule out vitamin deficiencies, thyroid problems, infections, and autoimmune markers. In younger individuals, genetic testing may be indicated if hereditary memory disorders are suspected.

Importantly, early diagnosis allows for timely intervention and better long-term outcomes. Recognizing that mental disorder memory loss can masquerade as dementia—or vice versa—empowers both clinicians and families to seek appropriate care.

Treatment Options for Memory Disorders

Treating a memory disorder depends heavily on its underlying cause. In neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, treatment aims to slow progression and manage symptoms. FDA-approved medications such as donepezil, rivastigmine, and memantine offer modest benefits in memory and function. Newer drugs targeting beta-amyloid and tau proteins are also in development.

Cognitive rehabilitation therapies involve structured activities designed to enhance memory skills. These programs often include memory exercises, organizational strategies, and compensatory techniques like using notes, alarms, and planners. Occupational therapy may also play a role in helping individuals adapt to memory loss in their daily routines.

Lifestyle interventions are increasingly emphasized in memory disorder treatment. Regular physical activity, a Mediterranean-style diet, social engagement, and cognitive stimulation have all been shown to support brain health and potentially delay cognitive decline. Sleep quality is particularly important, as sleep is vital for memory consolidation.

In reversible cases—such as vitamin B12 deficiency, medication side effects, or thyroid dysfunction—treating the underlying problem can significantly restore memory function. For trauma-related memory loss, treatment may involve neurorehabilitation, psychotherapy, and careful pharmacological support.

Assistive technologies like digital reminders, voice assistants, and smart devices can enhance independence and reduce caregiver burden. For some, participation in clinical trials offers access to experimental therapies and innovative care strategies.

Addressing Memory Loss from Mental Disorders

When memory impairment stems from a psychiatric condition, treating the mental illness often improves cognitive function. For example, in depression-related memory loss, antidepressant medications, psychotherapy, and behavioral activation can alleviate symptoms. As mood improves, so often does memory and attention.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has proven effective in helping patients with mental disorder memory loss develop adaptive coping strategies. In anxiety disorders, CBT can help reduce intrusive thoughts and hyperarousal, creating cognitive space for memory processes to resume normal functioning.

Antipsychotic medications are central to managing schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, but their impact on memory is complex. While they may improve certain symptoms, some medications can also dull cognition. In recent years, atypical antipsychotics with more favorable cognitive profiles have been introduced, and treatment plans are increasingly personalized to balance symptom control with mental sharpness.

Psychosocial interventions—such as structured routines, peer support, and environmental modifications—can be especially helpful. Educating families and caregivers about mental disorder memory loss fosters understanding and patience while providing tools to support the individual’s autonomy.

Mindfulness practices and relaxation techniques are showing promise as adjuncts to traditional therapies. These approaches help calm the nervous system, improve focus, and foster present-moment awareness, which can indirectly support memory.

Neuroplasticity and the Future of Memory Rehabilitation

One of the most exciting frontiers in memory research is neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to rewire itself. Studies have shown that even in individuals with significant memory impairment, targeted cognitive training can lead to functional and structural brain changes. This has led to the development of computerized memory training programs and immersive virtual reality environments designed to challenge and stimulate the brain.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) are being investigated for their potential to enhance memory circuits through non-invasive brain stimulation. While still experimental, early findings are encouraging, particularly for patients with mild cognitive impairment or depression-related memory deficits.

Pharmacological enhancement of memory is another area of focus. Researchers are exploring the role of nootropics—substances that may improve cognitive function—and neurotrophic factors that promote neuronal growth and survival. Although these treatments are not yet mainstream, they signal a shift toward proactive brain care.

Genetic studies may one day allow for highly personalized treatment of memory disorders. By understanding individual risk profiles and neural vulnerabilities, clinicians could tailor interventions to maximize effectiveness and minimize side effects.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the difference between a memory disorder and normal forgetfulness?

A memory disorder involves persistent, often progressive, impairments that interfere with daily life and functioning. Unlike normal forgetfulness, which may involve occasionally misplacing items or forgetting names, a memory disorder disrupts the ability to form new memories or retrieve existing ones. These disorders are often linked to neurological damage or disease, and the deficits tend to worsen over time. Normal forgetfulness does not typically impair a person’s independence or ability to perform daily activities. Recognizing the distinction is crucial for seeking appropriate diagnosis and care.

2. How does mental illness lead to memory loss?

Mental illnesses such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia can affect memory by disrupting attention, emotional regulation, and executive function. For instance, depression may reduce motivation and concentration, making it difficult to encode memories effectively. Anxiety can flood the brain with stress hormones that interfere with memory consolidation. In schizophrenia, structural brain abnormalities and neurotransmitter imbalances directly impair memory. These effects may fluctuate with symptom severity, and they are often reversible with proper treatment and stabilization.

3. Can someone have both a memory disorder and a mental disorder?

Yes, it is entirely possible for an individual to suffer from both a memory disorder and a mental disorder simultaneously. For example, a person with Alzheimer’s disease may also experience depression or anxiety, complicating diagnosis and treatment. Likewise, individuals with schizophrenia may develop neurodegenerative conditions as they age. When these conditions co-occur, comprehensive care is essential, involving neurologists, psychiatrists, neuropsychologists, and support networks to address the full spectrum of needs.

4. Are memory problems caused by stress permanent?

Memory problems caused by stress are usually temporary and reversible. Chronic stress elevates cortisol levels, which can impair the hippocampus—the brain region critical for memory. When stress is reduced through therapy, lifestyle changes, or medication, memory function often improves. However, prolonged exposure to high stress can lead to more lasting damage, particularly if it coexists with other risk factors such as poor sleep, substance use, or untreated mental illness. Early intervention is key to preventing long-term cognitive consequences.

5. How is memory loss diagnosed when mental illness is also present?

Diagnosing memory loss in the context of mental illness requires a multidisciplinary approach. Clinicians perform thorough histories, cognitive screening, psychiatric assessments, and sometimes neuroimaging. Neuropsychological testing is particularly valuable in distinguishing between primary memory disorders and cognitive symptoms secondary to psychiatric illness. Understanding the temporal relationship between mood symptoms and memory deficits can also provide diagnostic clarity. Effective diagnosis ensures appropriate, targeted treatment and improves outcomes.

6. Can medications for mental health affect memory?

Yes, some medications used to treat mental health conditions can affect memory. Benzodiazepines, commonly prescribed for anxiety, can cause short-term memory loss, especially in older adults. Antipsychotics and mood stabilizers may also dull cognition in some individuals. However, untreated mental illness can cause more severe cognitive impairment over time. Clinicians weigh these factors carefully and aim to select medications that balance symptom relief with cognitive preservation. Regular follow-up helps fine-tune treatment for optimal results.

7. What therapies can help improve memory in psychiatric patients?

Therapies that address both mental health and cognitive function are most effective. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), memory training exercises, mindfulness meditation, and structured routines can support memory by reducing cognitive load and improving focus. For some individuals, group therapy or occupational therapy provides additional structure and social reinforcement. Psychiatric stabilization through medication can create the conditions necessary for cognitive rehabilitation to succeed. These multimodal approaches are increasingly favored in clinical practice.

8. Is memory loss from depression reversible?

In many cases, memory loss due to depression is reversible. As depressive symptoms improve through therapy and/or medication, memory function often returns to baseline. However, if depression is prolonged or severe, cognitive deficits may persist even after mood improves. This phenomenon, known as “cognitive residuals,” may require targeted cognitive rehabilitation. Encouragingly, many patients regain significant memory function over time with comprehensive treatment and support.

9. How does trauma affect memory?

Trauma affects memory in complex ways. Some individuals may experience intrusive memories or flashbacks, while others may develop dissociative amnesia, blocking out parts of the traumatic event. Chronic trauma can alter brain structures like the amygdala and hippocampus, leading to fragmented or impaired memory processing. PTSD, a condition resulting from trauma, often includes both hyperactive recall and memory gaps. Trauma-informed therapy is essential to help individuals process and integrate their experiences in a healthy way.

10. What are the first signs of a memory disorder?

Early signs of a memory disorder include difficulty remembering recent events, repeating questions or stories, struggling to follow conversations, and misplacing items frequently. These symptoms may be accompanied by changes in mood, confusion, or withdrawal from activities. If these signs interfere with daily life, professional evaluation is warranted. Early detection allows for more effective intervention, whether the cause is a neurodegenerative disease, a medical condition, or a psychiatric illness.

Conclusion

Memory is more than a cognitive function—it is the foundation of human experience. When memory begins to fail, whether due to a memory disorder or as a symptom of mental disorder memory loss, the impact can be profound. Understanding the nuanced differences between neurological and psychiatric causes of memory loss is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. As science progresses, our ability to detect, manage, and potentially reverse memory impairment is improving. With the right interventions—ranging from medication and therapy to lifestyle changes and technological aids—individuals can reclaim cognitive function, maintain independence, and enhance quality of life. In a world where mental and neurological health are increasingly interconnected, a comprehensive, compassionate, and scientifically informed approach is not just beneficial—it is imperative.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.